- Home

- Mary Malloy

The Wandering Heart

The Wandering Heart Read online

The Wandering Heart

Mary Malloy

A LeapSci Book

Leapfrog Science and History

Leapfrog Press

Teaticket, Massachusetts

The Wandering Heart © 2009 by Mary Malloy

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a data base or other retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

A LeapSci Book

Leapfrog Science and History

Published in 2009 in the United States by

Leapfrog Press LLC

PO Box 2110

Teaticket, MA 02536

www.leapfrogpress.com

Distributed in the United States by

Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

St. Paul, Minnesota 55114

www.cbsd.com

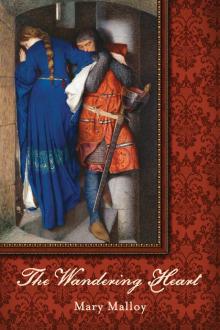

Cover Painting: The Meeting on the Turret Stairs

Frederic William Burton (1864)

Courtesy of the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

First Edition

ISBN 978-1-935248-03-3

This book is dedicated to my mother,

Dolores Malloy,

who inspired me

first to read and then to write.

NOTE TO READERS:

This edition of The Wandering Heart includes a reader’s guide featuring an extensive interview with the author. This section begins at the end of the book.

That anxious torture may I never feel,

Which, doubtful, watches o’er a wandering heart.

—Mary Tighe (1772-1810)

Contents

May, 1887

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

The Author

An Interview with Mary Malloy

May, 1887

Elizabeth Hatton was just nineteen years old when she threw herself off the roof of her family home. The maid, dusting in the library below, was the same age.

Elizabeth screamed as she fell as if, in midair, she’d reconsidered jumping and realized her mistake. The maid heard the scream, and then the awful sound as Elizabeth hit the flagstones of the terrace. Within a minute she was at Elizabeth’s side, gently holding her hand and trying to comfort her with soft meaningless words.

She knew Elizabeth would be dead very soon; everything about her seemed broken. Head and neck, legs and arms, were all at impossible angles, and a bit of jagged bone was visible coming through her mangled calf. A pool of blood spread rapidly across the carefully cut stones under her head. Elizabeth gasped several times for breath, but seemed unable to make the air penetrate all the way to her chest. Her eyes were locked on the maid’s when she made a last feeble attempt to breathe, then her pupils expanded rapidly and she went completely still.

As she reached out to close the dead eyes, the maid thought what a stupid, stupid, waste. Until this moment, she had thought Elizabeth Hatton the most fortunate of creatures. “Wouldn’t I have known what to do with such a life,” she thought. Elizabeth had sparkled with it: pretty, clever, beloved by her family, she seemed to have everything. She had never known want, never had to work. She could do what she wanted, go where she wanted, she had access to books and art and music. And she had thrown it all away because of a young man who was, in the maid’s opinion, dull, shallow, spoiled, and stupid. All his wealth, position, and good looks could not disguise his worthlessness.

Elizabeth’s last cry had been heard in the far corners of the house and now others began to emerge through the doors of the library onto the terrace. The first to arrive was Edmund. His sister’s scream brought him running at full speed out of the house, but he came to an abrupt stop when he saw the horrible scene. He collapsed to his knees beside Elizabeth’s body, moving his hands over her as if there might be something he could do, though he knew there was not. He hardly noticed the maid until she reached out and gently placed his dead sister’s hand in his.

He looked up, directly into the eyes of the maid. In the four years she had lived in the house, this was the first time he had ever met her gaze. His grey eyes were filled with fear and a wild grief.

Looking back, the maid could not help but note how much he looked like his sister lying dead between them. To think that on this day, of all days, the brother and sister had each, for the first time, really looked at her. Had they noticed that she was, like them, a human being?

She rose to leave as others from the household arrived. Edmund touched her arm to hold her back.

“Wait,” he said. “Did she say anything?”

The maid shook her head.

“May we speak later?” he asked.

She nodded.

As she went back into the house she couldn’t help thinking that there would be a mess of blood and brains to clean up.

Chapter 1

The reading room in the library was Lizzie’s favorite place on campus. Part of the attraction was the cathedral-like space, but mostly it was the light. Green-shaded lamps cast pools of light onto the polished wood of the tables but left much of the high-ceilinged room in a comfortable dimness. The tall windows were filled with small diamond-shaped panes of wavy glass which filtered the sunlight into a pleasant haze, but nothing viewed through these windows could be seen clearly unless you stepped right up and put your face almost against the cool surface of lead or glass. There were no sharp edges in the room. It had a spaciousness and softness which created exactly the atmosphere that Lizzie thought was most appropriate for contemplation and study. In such a room she could slip easily into the past.

In the real world, Elizabeth Manning was a history professor at St. Patrick’s College in Charlestown, Massachusetts. In the big canvas book bag slung over her shoulder were papers to grade, bills to pay, an article to finish, and a letter. It was the letter which brought her here; this letter held the potential to take her across time and around the world.

Lizzie’s friend, Jackie Harrigan, was head of the reading room and had an imposing perch at one end of it. Her desk was raised on a pedestal several steps above the floor to give her a view of her whole domain. Jackie raised her head when the door opened, ready to shoot her serious librarian expression at whoever entered, but she smiled when she saw her friend. The two women were the only occupants, and Lizzie consequently burst into song. She had once commented to a horrified Jackie that the acoustics of the room were better suited for singing than silence, and ever since had felt compelled to prove it on those rare occasions when they were alone there. For Jackie’s benefit, Lizzie mostly sang bawdy Irish songs, and as she proceeded up the side aisle of the lon

g room she progressed through several days of the “Seven Drunken Nights.”

“Professor Manning!” Jackie scolded. “Must I remind you that this is a library?” It was her stock response to Lizzie’s singing and always made Lizzie sing even louder.

The two women knew each other well enough, and saw each other often enough, that they seldom bothered to exchange pleasantries, but burst headlong into the middle of conversations. Today, Lizzie was anxious to get Jackie’s opinion of the letter, and she had it out of her bag and onto the librarian’s desk before either of them said hello.

“Here’s something interesting,” she said, “a letter from one George F. R. Hatton of Hengemont, Somerset, England.” She tapped the envelope with her finger. “He has a coat of arms!”

Jackie turned the envelope around to examine it. On the shield of the crest was a heart being pierced by a long cross-shaped sword. Below it a curving ribbon held the motto “Semper Memoriam.”

The librarian looked up at her friend. “Yuck!” she said. “A sword stabbing a heart? That’s pretty graphic. It hardly seems like they need the motto there to tell you to remember it.”

She pulled the contents from the envelope and quickly read the letter aloud. It was an invitation to Lizzie to come to George Hatton’s home in the west of England and advise him on a collection of artifacts made by his ancestor, Lieutenant Francis Hatton of the British Royal Navy. The collection had been made on the third voyage of Captain James Cook to the Pacific Ocean. Jackie’s tone changed as she read the letter.

“This is a wonderful opportunity for you, Lizzie,” she said. “A Cook collection!”

Lizzie nodded. “Here’s the best part,” she said, pulling two photocopied pages from underneath the letter. “The guy kept a journal and it has never been published.”

Jackie quickly scanned the pages. She was one of the few people Lizzie knew who could read old handwriting as well as she did herself.

“Did you know about this when you were working on your book?”

“No!” Lizzie said emphatically. “No one did. It isn’t in any bibliography, I’ve never even heard of it.” She sighed with frustration, then took the pages from Jackie and began to point out certain passages. “It’s an especially good one, too,” she continued. “Francis Hatton was a wonderful writer, and a sympathetic and careful observer. I’m practically in love with him already, and I’ve only seen two pages.”

Jackie looked again at the letter and its envelope. “Interesting that he invites you to stay at his house,” she said, quoting a passage from the letter which promised Lizzie a “comfortable place to live and work” for however long she could spare for the project. “A castle perhaps?” Jackie continued, raising an eyebrow. “Or a stately home?”

Lizzie pointed to the return address, which said simply “Hengemont, Somerset.”

“I think that’s the name of his house,” she said, beaming. “A house with a name!”

Jackie smiled and murmured under her breath about the dangers of reading too many British novels before asking her friend if she intended to accept the invitation.

“Of course,” Lizzie answered quickly. “Martin and I talked about it a bit last night, and I’ve pretty much decided to go during the January break.” She folded the pages. “I just want to find out what I can about Lieutenant Hatton before I jump off the deep end.”

“Help yourself,” Jackie said, gesturing toward the door to the library stacks. “You know better than anyone where the Cook material is.”

Lizzie picked up her bag and was reaching for the letter when Jackie asked if she could keep it for a few minutes. “Let me see what I can find out about George Hatton while you look up his ancestor,” she said.

Lizzie smiled her thanks and headed into the dusky world where the library kept the rare book collection on row after row of metal shelving. She knew exactly where to find the narrative of Captain James Cook’s third voyage to the Pacific Ocean and she pulled it off the shelf on the way to her study carrel. She turned immediately to the crew list and his name jumped out at her: Francis Hatton, First Lieutenant on HMS Resolution. Among his shipmates were William Bligh and George Vancouver.

She began to compare the two pages from Francis Hatton’s journal with the published account of the voyage. They described activities of the English expedition on the coast of British Columbia in 1778. Charming, well-written, and filled with detail, Hatton’s text caught the immediacy of the exotic situations in which he found himself, and totally captivated Lizzie. She alternated between feeling a thrill of discovery and frustration that she hadn’t known about this material when she was working on her dissertation and the book which resulted from it. In fact, she wondered again, why hadn’t Hatton’s journal ever been published? Every known scrap of manuscript material from Cook’s three voyages had been pored over by scholars and publishers for two hundred years.

She had been working for half an hour when Jackie came down the spiral iron staircase with a stack of papers in her hand.

“I’m off to lunch,” she said, handing them to Lizzie, “but here is some stuff on that Hatton guy. He has a rather interesting family.” Beneath the letter were several photocopies topped by the title page to Burke’s Peerage.

“You are a peach,” Lizzie said. “I would never even have thought to look him up there.”

“He’s a Lord,” Jackie said with a mock British accent.

Lizzie grinned at her friend. The two women had met in an Irish language class at St. Pat’s and spent many late afternoons sharing pints of Guinness in the pub on campus. Their early relationship had been defined by tipsy explorations of the British victimization of their Hibernian ancestors, a subject Jackie returned to often.

“Thank you for warning me,” Lizzie said, bowing. “I’ll be sure to take my groveling clothes.”

Jackie handed her the papers. “I think you’ll find this very compelling reading, mo chara.”

“Do they mention Francis Hatton’s voyage with Cook?”

“Absolutely,” Jackie answered. “He gets as much ink as any of them.”

“So don’t you think it’s strange that his journal was never published?”

Jackie agreed that it was odd. “Could he have been hiding something that he didn’t want made widely known?”

This had not occurred to Lizzie, and she thought it unlikely. “Like what?”

“I don’t know,” Jackie mused. “Maybe an affair with a Polynesian woman?”

“All the British sailors had affairs with Polynesian women!” Lizzie answered with a derisive laugh. “And I don’t think they were all that embarrassed about it.” She thought for another moment. “Of course they didn’t usually document that kind of behavior in their own journals—they saved those descriptions for the actions of the other guys!”

The two women smiled at each other.

“Men!” Jackie sighed. “There were probably dozens of little Hattons scattered across the Pacific after the voyage.”

“Well, not surprisingly, George Hatton did not choose to share that with me in my first encounter with the information,” Lizzie said. “It will have to wait until I get to England and see the rest of the journal.”

“Something to look forward to beyond the usual details of wind and weather,” Jackie responded, turning to climb back up the stairs. “See you for lunch on Thursday,” she said as she left.

Lizzie felt the small stack of pages in her hand. There wasn’t time to look at them all before she had to be back in her office to meet with students.

Before she closed the volume of Cook’s Voyages, she went back a last time to the crew list and ran her finger softly across the name “Francis Hatton, First Lieutenant.” She knew already that he was a man she wanted to know better. Reading those few pages from his journal had been like the first introduction to a person who would become a fast friend. The rel

ationship held great promise for developing into something deeper, more meaningful, even important. She felt a tingle of excitement knowing that before long she could be living in his house, walking where he had walked, reading his private papers.

There were times when Lizzie found the past very tangible, when a connection was formed between herself and some person long dead, or some event long forgotten. Then a feeling was evoked which could not be duplicated by any other kind of experience. It was for those moments that she had become a historian, and she felt very strongly that this was the beginning of a string of those moments.

Chapter 2

As she drove home through the rush-hour traffic that afternoon, Lizzie thought of her conversation with Jackie. Her friend knew her very well, but neither she nor Lizzie herself had ever really plumbed the depths of Lizzie’s conflicting feelings of attraction to and condemnation of the English aristocracy. In fact she did feel all the romantic possibilities that George Hatton’s invitation held. She had no desire to live in the past, but she loved to vicariously luxuriate in it. Jackie would, she knew, consider any enjoyment of the Hatton experience a betrayal of her Irish heritage.

When she got home she quickly changed into sweat pants and an old shirt and went to find her husband in his studio. Over the years Lizzie had lost too many sweaters to enthusiastic painty embraces to risk going there directly, but she was eager to resume the discussion they had started the evening before about the possibility of her going to England.

“Hello, my love,” Martin called to her as she opened the door to his studio. He was on a ladder, working on a canvas that covered one entire wall of the room.

She sat down in the chair that was reserved for her; it was the only flat surface in the room that was not covered with bits of paper, chalk, crayons, cups of cold coffee, photographs, tape, brushes, or tools. It occurred to Lizzie as she pondered his clutter that they might be too much alike to live together successfully. She leaned back and watched the New York skyline emerge under her husband’s deft hands. She loved to watch him work and she knew that serious conversation would have to wait until his current frenzy of inspiration was spent.

Paradise Walk

Paradise Walk The Wandering Heart

The Wandering Heart The Wonder Chamber

The Wonder Chamber